Bluetongue virus

What is Bluetongue?

Bluetongue (BT) is an infectious disease, transmitted mainly by midges of the genus Culicoides, that affecs different species of ruminants. The agent is the Bluetongue virus (BTV), an Orbivirus from which more than 30 possible serotypes have been described.pes have been described.

Bluetongue (BT) is an infectious disease, transmitted mainly by midges of the genus Culicoides, that affecs different species of ruminants. The agent is the Bluetongue virus (BTV), an Orbivirus from which more than 30 possible serotypes have been described.pes have been described.

BTV affects ruminants, both domestic and wild. Sheep are considered to be the main host, since it is the species that develops the disease, presenting high rates of mortality and morbidity. Moreover, other non-ruminants may be infected by BTV, such as shrews or dogs.

For the typical serotypes (1-24), the main route of transmission is by midges of the genus Culicoides, although not all species in this genus, which consists of more than 1400 species, are capable of transmitting BTV. Other epidemiologically less relevant routes of transmission have been described: semen, embryos, transplacental and iatrogenic.

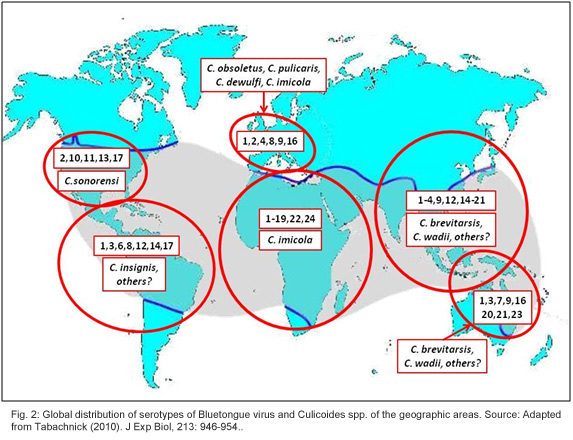

The presence of the disease is directly related to the distribution of competent vectors. This distribution is closely linked to ecological and climatic conditions, which determine the distribution and abundance of the vector species. Currently, the distribution of competent vectors is located in 65°N latitude in Europe. The maximum activity period of the vector in this continent occurs in late summer or early fall. Climate change is one of the determining factors in the increased expansion the disease.

Historical development and status in Europe

Bluetongue virus (BTV) was described for the first time in South Africa in the early twentieth century. The disease distribution was limited to Africa, where the infection was endemic in wild ruminants, until the disease was described in Cyprus, in 1943. Since then, BTV has spread across the Mediterranean Basin and other regions such as USA, Canada or Australia, always determined by the presence of competent vectors.

Currently, the geographic distribution of the disease encompasses a worldwide distribution. However, until 2006 it was restricted to latitudes between parallels 35º N and 40º S (Figure 2).

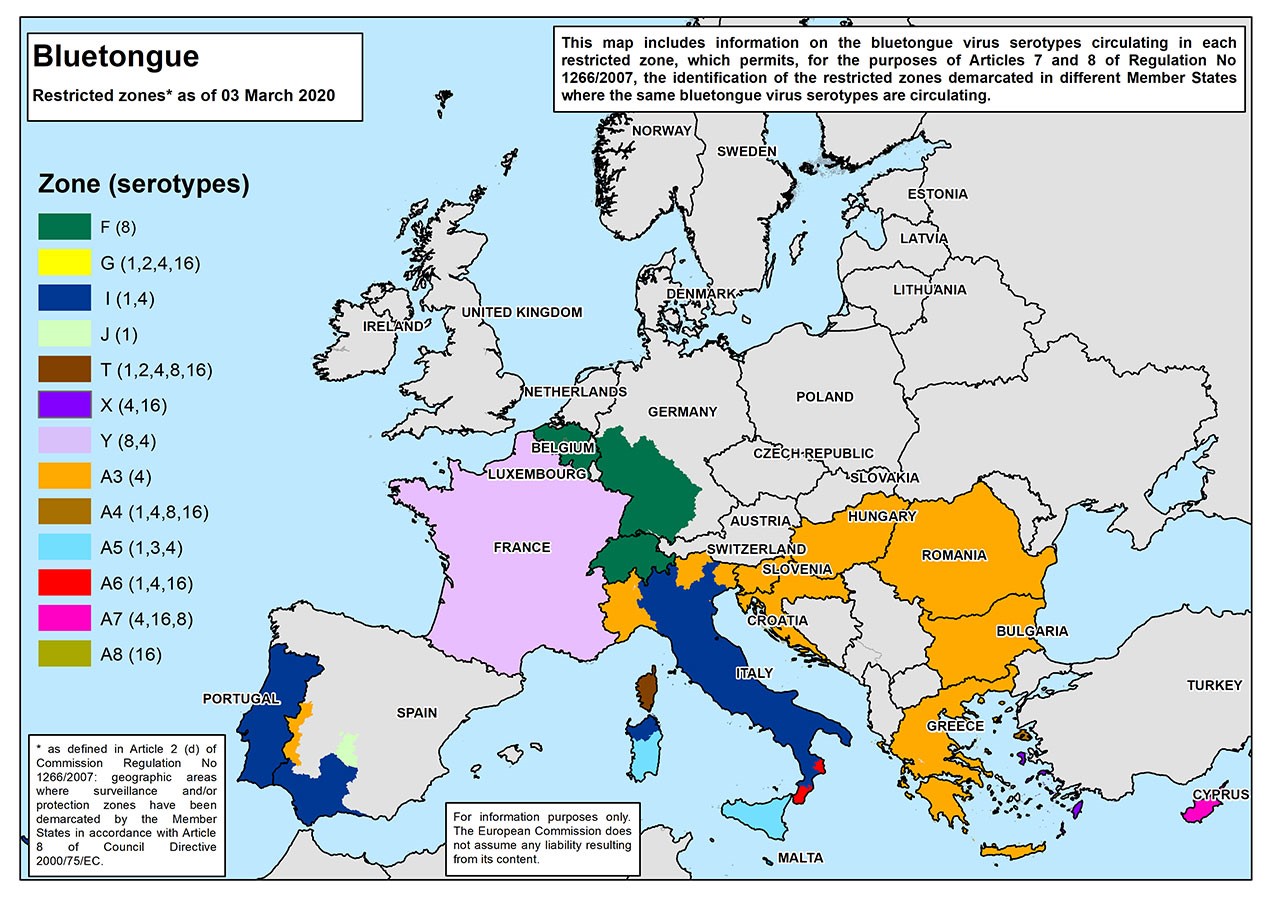

In Europe, at the beginning of the century the disease was located in southern countries until 2006, particularly in the Mediterranean Basin, where serotypes 1, 2, 4, 9, 10 and 16 were reported. In August 2006, the first outbreak of serotype 8 was notified in the Netherlands. The disease spread rapidly to Germany, Belgium, France and Luxembourg. This serotype had never been reported in Europe and these regions had never been affected by BTV. In subsequent years (2007 and 2008), the disease spread to Switzerland, Denmark, Czech Republic and the United Kingdom, reaching Spain in January 2008.

Furthermore, in 2007 the serotype 1 was introduced in Spain, also spreading to Portugal and Italy. The following year, serotype 6 was notified in the Netherlands and Germany, and serotype 25 in Switzerland. Serotype 11, was found in 2009 in Belgium. The outbreaks of both serotypes 6 and 11 occurred by vaccine strains.

After years of epidemiological silence, in 2015 serotype 8 reappeared in France. Later in 2018, it spread to Switzerland and Germany; and in 2019 to Belgium. In 2017 serotype 4 was introduced in France and serotype 3 was reported in Sicily. A year later serotype 3 appeared in Sardinia. Likewise, in 2018 serotype 1 was extended from Spain to Portugal.

In addition, in recent years several strains of atypical BTV serotypes have been identified circulating in European territory.

Currently, BTV serotypes 1, 2, 4, 8, 9 and 16 have been circulating in the European Union.

Fig. 3: Restricted zones for the different BTV serotypes circulating in Europe (march 2020). Source: European Commission.

Fig. 3: Restricted zones for the different BTV serotypes circulating in Europe (march 2020). Source: European Commission.

Evolution of the disease in Spain in the XXI century

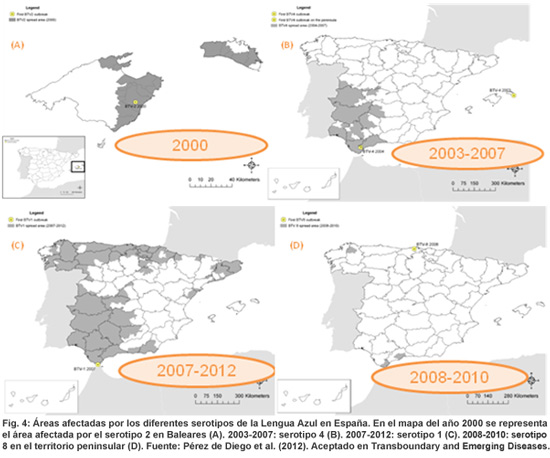

Since 2000 until now, Spain has reported four Bluetongue Virus (BT) serotypes (serotypes 2, 4, 1 and 8). Serotypes 2, 4 and 1 seem to have been introduced into Spain by infected midges carried by the wind from northern Africa. However, the route of introduction of serotype 8 may be due to trade of infected animals from the central and northern Europe. Control measures have been based on vaccination and restriction of animal movement from affected to non-affected areas, achieving the eradication on several occasions (Balearic Islands in 2002 and 2005; mainland Spain in 2009).

In 2007, BTV-1 was introduced in Spain and during the initial years of virus circulation in the country, it suffered a significant geographical expansion; reaching northern regions. As of 2008, the entire peninsular Spain was a restriction zone for BTV-1. In years to come, the number of reported outbreaks and geographical extent were reduced. From 2018 to mid-2020, no viral circulation of this serotype has been detected.

BTV- 4 has been introduced twice in mainland Spain. The first in 2006, being Spain declared free of BTV-4 in 2009. In 2010, it reappeared and. to date. outbreaks continue to be reported every year.

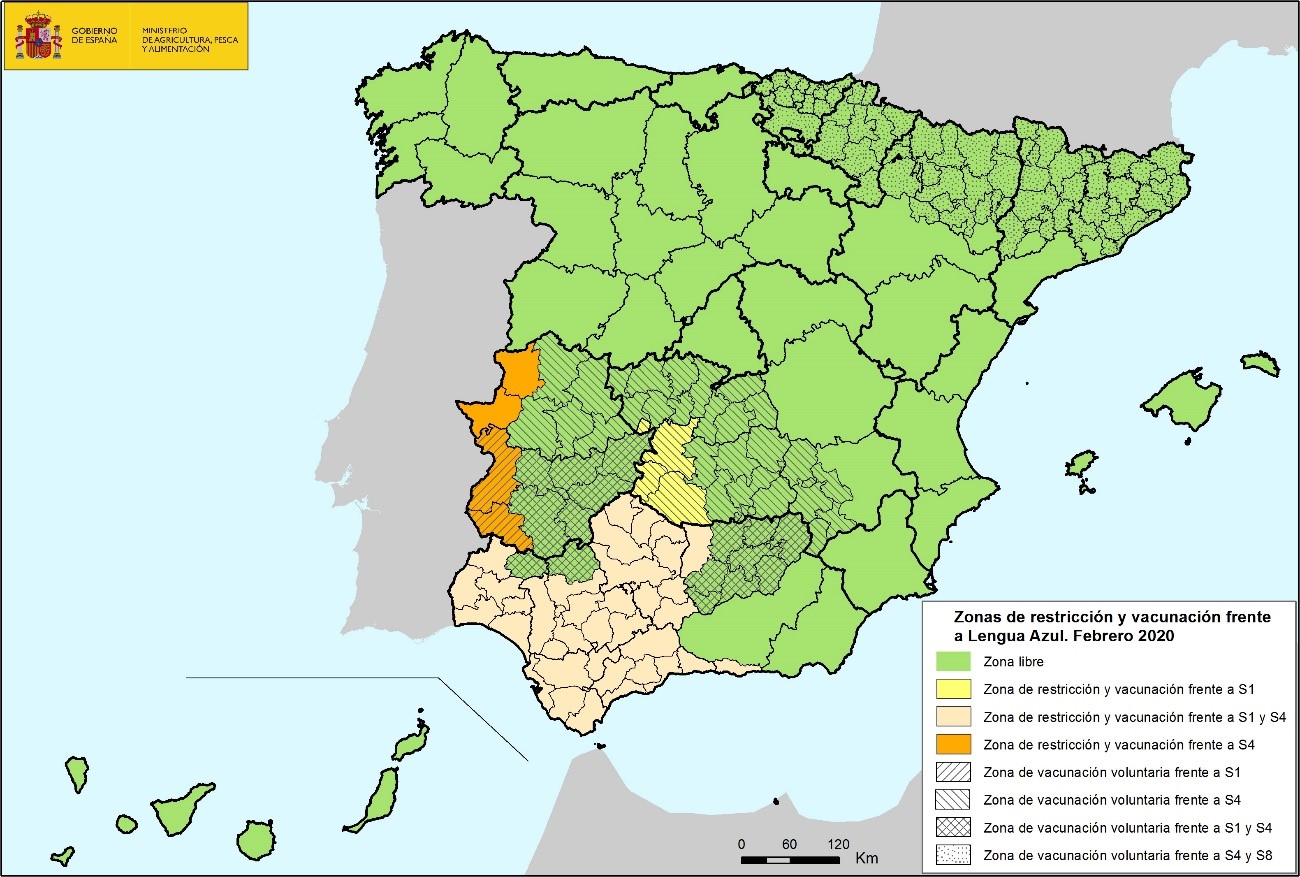

The restriction zones for BTV-1 and 4 of Spain as of June 2020 are located in the south-west and center-west of the peninsula.

Fig. 6: Restricted zones for the different BTV serotypes (February 2020)

Source: Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación (MAPA), 2020

Diagnosis of Bluetongue

With the emergence of an outbreak, early suspicions are based on characteristic clinical signs and on the presence of vectors in the outbreak area. However, laboratory testing is required for confirmation of the diagnosis. The laboratory techniques are prescribed by the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) in Chapter 2.1.3 of the Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals 2011). In Spain, the diagnosis of this disease must be made in the diagnosis laboratory of the Autonomous Communities or by the National Reference Laboratory for Bluetongue virus (BTV), Laboratorio Central de Veterinaria de Algete. The diagnosis is based on virus isolation and identification from blood and tissue samples and in the detection of antibodies in unvaccinated animals:

Serological tests:

- Competitive ELISAs to specifically detect anti-BTV antibodies. This methodology is available in National Reference Laboratory.

- The serotype-specificity of antibodies in sera is determined by neutralization tests.

Identification of agent:

- Virus isolation in embryonated hens’ eggs or in cultured cells.

- Detection, identification and characterization of viral genome by RT-PCR: This technique is available in Laboratories Bluetongue diagnosis of autonomous communities. In addition, the National Reference Laboratory has RT-PCR techniques specific to different serotypes (serotypes 1, 4 and 8).

Prevention and control of Bluetongue Virus

World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) established in Terrestrial Animal Health Code (Chapter 8.3, Bluetongue) what kind of measures should be carried out against Bluetongue virus (BTV). These measures are included in the European Union (EU) (Directive 2000/75/EC) and national legislation (Manual Práctico de Operaciones en la Lucha Contra la Lengua Azul - Spanish). The recommendations contained in these legislations are based on:

- Notification to the competent authorities of all suspected cases.

- The total sacrifice on the farm is not justified as eradication measure.

- Restriction of animal movement from the farm or farms concerned.

- Establishment of a protection and surveillance zones around the farm or farms concerned, 100 and 50 kilometers, respectively. These distances are higher than those established for other diseases EU listed, because is transmitted by mosquitoes. The size of these areas can be modified by geographical, climatic and entomological conditions.

- Confinement of animals during the maximum activities of vectors and vector control measures using insecticides and repellents on the environment, in the accommodation of animals and the animals themselves.

- Implementation of clinical, serological, epidemiological and entomological in the areas of protection and surveillance zones established around the outbreaks.

- Vaccination programs of all host of BTV locate in the protection zone.

- Programs entomological surveillance through trapping, allow us to know the species of Culicoides which can transmit the disease.

- Serological surveillance programs allow early detection of the presence of the disease.

Vaccination is the most effective measure to minimize losses associated with the disease, eventually interrupt the cycle of the animal to the vector and allow the eradication of the disease. Due to the existence of many serotypes should be used vaccines against one or several serotypes isolated in the outbreak. There are several types of vaccines against Bluetongue:

- Live attenuated vaccine polyvalent or monovalent.

- Inactivated vaccine polyvalent or monovalent.

Vaccination in Spain

Bluetongue vaccination is recommended by the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) and the European Union (Directive 2000/75/EC) since an effective method for the Bluetongue virus (BTV) eradication. This technique stimulates the immune system preventing viral replication in animals, therefore decreases the viral circulation. Furthermore, it facilitates the movement of animals of susceptible species from restricted zone to free area with adequate sanitary guarantees. Finally, this goal is the final eradication of the disease.

In Spain, we have used two types of vaccines for the disease control: live vaccines monovalent used from 2000 until 2006; and inactivated vaccines monovalent since 2006, or polivalent (serotypes 1 and 4; serotypes 1 and 8), since 2009. Currently, the inactivated vaccines are the only ones in use. Vaccinations of the different provinces are established according to the restriction zones established by the Spanish Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Environment (MAGRAMA).

Since 2000, through the use of prophylactic measures, especially vaccination campaigns, has been eradicated serotype 2 in 2002 (Balearic Islands), serotype 4 in 2005 (Balearic Islands) and serotype 4 in 2009 (Peninsula).

From June 30, 2011, vaccination was voluntary at the discretion of the owner of the farm, who also became responsible for assuming its economic cost. It was not until 2015 that compulsory vaccination was extended in all the restriction zones for the different serotypes. Currently, vaccination against BTV in Spain is regulated by the regulation AAA/1424/2015, which establishes specific protection measures against bluetongue, which has recently been modified by the regulation APA/206/2020. Here mandatory and voluntary vaccination zones are defined in areas close to the restriction zones, with respect to serotypes 1 and 4 (see figure 6).

PhD Thesis

- Estudio comparativo de la respuesta inmune inducida por dos tipos de vacunas (VLP e inactivada) frente al virus de la Lengua Azul en ganado ovino. Ana Cristina Pérez de Diego Camacho. Facultad de Veterinaria. Universidad Complutense. Junio 2012. Sobresaliente Cum Laude por Unanimidad (Mención Europea)

- Desarrollo de un modelo epidemiológico para el estudio de la transmisión de lengua azul en España por su vector biológico. Amparo Martínez Salvador. Facultad de Veterinaria. Universidad Complutense. Julio 2004. Sobresaliente Cum Laude.

Publications

- Aguilar-Vega C., Fernandez-Carrion E., Lucientes J., Sanchez-Vizcaino JM. "A model for the assessment of bluetongue virus serotype 1 persistence in Spain". PLoS ONE, 15(4):e0232534. 04/2020. (A)

- Aguilar-Vega C., Fernandez-Carrion E., Sanchez-Vizcaino JM. "The possible route of introduction of bluetongue virus serotype 3 into Sicily by windborne transportation of infected Culicoides spp". Transboundary and Emerging Diseases, 66(4):1665-1673. 07/2019. (A)

- Fernandez-Carrion E., Ivorra B., Ramos AM., Martinez-Lopez B., Aguilar-Vega C., Sanchez-Vizcaino JM. "An advection-deposition-survival model to assess the risk of introduction of vector-borne diseases through the wind: Application to bluetongue outbreaks in Spain". PLoS ONE. 13(3):e0194573. 3/2018.

- Sanchez-Cordon, PJ., Perez de Diego, AC., Gomez-Villamandos, JC., Sanchez-Vizcaino, JM., Pleguezuelos, FJ., Garfia, B., del Carmen, P., Pedrera, M. "Comparative analysis of cellular immune responses and cytokine levels in sheep experimentally infected with bluetongue virus serotype 1 and 8". Vet Microbiol. 177(1-2):95-105. 5/2015

- Pascual-Linaza A.V., Martínez-López, B., Pfeiffer, D.U., Moreno, J.C., Sanz, C., Sánchez-Vizcaíno, JM. “Evaluation of the spatial and temporal distribution of and risk factors for Bluetongue Serotype 1 epidemics in sheep Extremadura (Spain), 2007-2011. Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 116(3):279-295. 9/2014.

- Ruíz- Fons, F., Sánchez-Matamoros, A., Gortázar, C., Sánchez-Vicaíno, JM. “The role of wildlife in bluetongue virus maintenance in Europe: Lessons learned after the natural infection in Spain”. Virus research. 182:50-8. 3/2014.

- De Diego, AC, Sánchez-Cordón, PJ, Sánchez-Vizcaíno, J.M. (2014) "Bluetongue in Spain: From the First Outbreak to 2012". Transbound Emerg Dis. 61(6): e1-e11. 12/2014.

- Pérez de Diego AC, Sánchez-Cordón PJ, Pedrera M, Martínez-López B, Gómez-Villamandos JC, Sánchez-Vizcaíno JM. "The use of infrared thermography as a non-invasive method for fever detection in sheep infected with bluetongue virus". The Veterinary Journal. 198(1):182-6. 10/2013.

- Zientara, S., Sánchez-Vizcaíno, JM. (2013) "Control of bluetongue in Europe". Vet Microbiol. I 26;165(1-2):33-7. 7/2013.

- Sanchez-Cordon PJ., Pedrera M., Risalde MA., Molina V., Rodriguez-Sanchez B, Nuñez A., Sanchez-Vizcaino, JM., y Gomez-Villamandos. (2013) "Potential Role of Proinflammatory Cytokines in the Pathogenetic Mechanisms of Vascular Lesions in Goats Naturally Infected with Bluetongue Virus Serotype 1". Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. 60(3):252-62. 6/2013.

- Galindo, RC, Falconi, C., López-Olvera, JR., Jiménez-Clavero, MA., Fernández-Pacheco, P., Fernández-Pinero, J., Sánchez-Vizcaíno JM., Gortázar, C., de la Fuente, J.,(2012) "Global gene expression analysis in skin biopsies of European red deer experimentally infected with bluetongue virus serotypes 1 and 8". Vet Microbiol. 161(1-2):26-35. 12/2012.

- Perez de Diego, AC., Sánchez-Cordón, PJ., de las Heras, A.I., Sánchez-Vizcaíno, JM (2012). "Characterization of the Immune Response Induced by a Commercially Available Inactivated Bluetongue Virus Serotype 1 Vaccine in Sheep". The Scientific World Journal. 2012 (ID: 147158, 8 pag.). 4/2012.

- Perez de Diego, AC., Athmaram, TN., Stewart, M., Rodriguez-Sanchez, B., Sanchez-Vizcaino JM., Noad R. y Roy P.(2012). "Characterization of Protection Afforded by a Bivalent Virus-Like Particle Vaccine against Bluetongue Virus Serotypes 1 and 4 in Sheep". PLoS ONE. 6(10):e26666. 10/2011

- Sánchez-Cordón, PJ., Rodríguez-Sánchez, B., Risalde, MA., Molina, V., Pedrera, M., Sánchez-Vizcaíno, JM., Gómez-Villamandos, JC. (2010). “Immunohistochemical Detection of Bluetongue Virus (BTV) in Fixed Tissue”. Journal of Comparative Pathology, 143 (1):20-8.

- López-Olvera, JR., Falconi, C., Fernández-Pacheco, F., Fernández-Piñero, J., Sánchez, MA., Palma, A., Herruzo, I., Vicente, J., Jiménez-Clavero, MA., Arias, M., Sánchez-Vizcaíno, JM., Gortázar, C.(2010). “Experimental infection of European red deer (Cervus elaphus) with bluetongue virus serotype 1 and 8”. Veterinary Microbiology, 145 (1-2): 148-152.

- Rodríguez-Sánchez, B., Gortazar, C., Ruiz-Fons, F., Sánchez-Vizcaíno, JM. (2010). “Bluetongue virus serotypes 1 and 4 in red deer, Spain”. Emerging Infectious Diseases 16 (3): 518-20.

- Zientara, S., Maclachlan, N.J., Calistri, P., Sánchez-Vizcaíno, JM., Savini, G. (2010). "Bluetongue vaccination in Europe". Expert Reviews Vaccines 9 (9), 989-991.

- Rodriguez-Sanchez, B., Sanchez-Cordon, P., Molina, V., Risalde, M., Perez de Diego, A., Gomez-Villamandos, JC., Sánchez-Vizcaíno, JM. (2010). “Detection of bluetongue serotype 4 in mouflons (ovis aries musimon) from Spain”. Veterinary Microbiology, 141, 164-267.

- Savini, G., MacLachlan, N.J., Calistri, P., Zientara, S., Sánchez-Vizacaíno, JM. (2008). “Vaccines against Bluetongue in Europe”. Comparative Immunology & Infecitious Diseases, 616, 1-21,

- Rodríguez-Sánchez, B., Iglesias-Martín, I., Martínez-Avilés, M., Sánchez-Vizcaíno, JM. (2008). "Orbiviruses in the Mediterranean Basin: Updated Epidemiological Situation of Bluetongue and New Methods for the Detection of BTV Serotype 4. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases, 55, 205-214.

- Makoschey, B., Beer, M., Zientara, S., Haubruge, E., Rinaldi, L., Dercksen, D., Millemann, Y., Von Rijn, P., de Clerq, K., Oura, C., Saegerman, C., Domingo, M., Sánchez-Vizcaíno, JM., Mehlhorn, H., Tamba, M., Thiry, E. (2008) “Bluetongue Control: A new challenge for Europe”.Berl Munch Tierarztl Wochenschr. Jul-Aug; 121 (7-8): 306-13.

- Agüero, M.; Arias, M.; Romero, L.; Zamora, MJ.; Sánchez-Vizcaíno, JM. (2002). Molecular differentiation between NS1 gene of a field strain bluetongue virus serotype 2 (BTV-2) and NS1 gene of an attenuated BTV-2 vaccine. Veterinary Microbiology 86 (4): 337-341.

- Roy, P.; Hirasawa, T.; Fernández, M.; Blinov V.M.; Sánchez-Vizcaíno Rodríguez,M. (1991). The complete sequence of the group-specific antigen, VP7, of african horsesickness disease virus serotype 4 reveals a close relationship to bluetongue virus. Journal of General Virology 72, 1237-1241.

Non indexed

- Pérez de Diego AC., Sanchez-Cordon PJ. y Sanchez-Vizcaino JM. "Evolução histórica e situação atual da língua azul em Espanha". Albèitar Portugal. Servet - Grupo Asis Biomedia. ISBN: 1646-1177. 7/2015

- Pérez de Diego, AC., Sánchez-Cordón, PJ., Sánchez-Vizcaíno, JM. (2015). “Evolución histórica y situación actual de la lengua azul en España”. Revista albèitar. Nº183. Marzo

- Cianci, C., Granero Belinchon, R., Picado Alvarez, R., Pino Carrasco, FJ., Rodrigo Campos, N., Tamayo Mas, E., Vázquez, M., Ivorra, B., Martínez-López, B., Ramos, A.M., Sánchez-Vizcaíno JM. (2011). “Impact of the climatic change on animal diseases spread: the example of bluetongue in Spain”. Revista Complutense de Ciencias Veterinarias 5(1):120-131.

- Sánchez-Matamoros, A., Martínez, M., Sánchez-Vizcaíno, JM. (2009). “Impacto de la vacunación en el control de la Lengua Azul”. Revista Complutense de Ciencias Veterinarias. 3 (2) 31-40.

- Pérez de Diego A.C., del Carmen P, Carvajal J., Sánchez-Vizcaíno JM. 2009 “Seguimiento clínico del ensayo de una vacuna VLP para os serotipos 1 y 1+4 de la lengua azul en ganado ovino.” Revista Complutense de Ciencias Veterinarias 3 (2). 69-78.

- Pérez de Diego A.C., Espinosa L., Sánchez-Vizcaíno JM. 2009 “Valoración de la producción de anticuerpos en un ensayo de vacunas VLP frente a los serotipos 1 y 4 de la lengua azul”. Revista Complutense de Ciencias Veterinarias 3 (2). 184-191.

- Martínez-López, B., Pérez, C., Baldasano, JM., Sánchez-Vizcaíno, JM (2009). “Bluetongue virus (BTV) risk of introduction into Spain associated with wind streams”. Proceeding, ISVEE XII.

- Sánchez-Matamoros, A., Grande San Miguel, A., Rodríguez Sánchez, B., Sánchez-Vizcaíno, JM. (2008). “Relación entre los Serotipos de Lengua Azul y su vector, en Europa y Cuenca Mediterránea”. Revista Complutense de Ciencias Veterinarias. 2 (2) 45-53.

- Sánchez-Cordón, P.J., Rodríguez-Sánchez, B., Pedrera, M., Risalde, M.A., Molina, V., Ruiz-Villamor, E., Sánchez-Vizcaíno, JM., Gómez-Villamandos, JC. (2008). “El virus de la lengua azul como modelo para el estudio de los orbivirus”. Anales, Vol.21 (1), Real Acadamia de Ciencias Veterinarias de Andalucía.

- Ciuéndez, R.; Sánchez-Vizcaíno, JM. (2007). “Papel de los animales salvajes en la lengua azul”. Revista Complutense de Ciencias Veterinarias. 1 (2), 192-199.

- Sánchez Matamoros, A.; Grande San Miguel, A; Cicuéndez, R; Sánchez-Vizcaíno, JM. (2007). “¿Cómo entró la lengua azul en el norte de Europa?”. Revista Complutense de Ciencias Veterinarias. 1 (2). 185-191.

- Martinez A., Sanchez-Vizcaino JM. "Características epidemiológicas de la lengua azul". Ovis, 95:9-15, Acalanthis Comunicaciones y Estrategias. 2005. (Outreach arcticle)

- Martinez A., de la Torre A., Sanchez-Vizcaino JM. "Distribución geográfica de la lengua azul". Ovis, 95:25-29, Acalanthis Comunicaciones y Estrategias. 2005. (Outreach arcticle)

- Martinez A., Sanchez-Vizcaino JM. "Métodos de diagnóstico de la lengua azul". Ovis, 95:31-35, Acalanthis Comunicaciones y Estrategias. 2005. (Outreach arcticle)

- Martinez A., Sanchez-Vizcaino JM. "Sistemas de control y lucha frente a la lengua azul en España". Ovis, 95:37-42, Acalanthis Comunicaciones y Estrategias. 2005. (Outreach arcticle)

- Martinez A., Aguayo S., Lucianes J., Sanchez-Vizcaino JM. "Vectores biológicos de la lengua azul". Ovis, 95:17-23, Acalanthis Comunicaciones y Estrategias. 2005. (Outreach arcticle)

- Blanco, E.; Arias, M.; Sánchez-Vizcaíno, JM. (2000). Improved indirect ELISA based on the 3ABC polyprotein for differential infection from vaccination in foot and mouth disease. European Commission for the control of FMD. Research group report 27, 211-221.

- León, M., Casal, J., Gomez-Tejedor, C., Sánchez-Vizcaíno, JM (1997). Simulation of the risk of airborne spread of foot and mouth disease virus from a high security laboratory release. Epidemiol santé anim., 31-32

- Laviada, M.D.; Babín, M.; Roy, P.; Sánchez-Vizcaíno, J.M. (1992). Adaptation and Evaluation of an Indirect ELISA and Immuno-Blotting Test for African Horse Sickness Antibody Detection. Bluetongue, African Horse Sickness and Related Orbiviruses. Proceedings of the Second International Symposium. Edited by Thomas E. Walton and Bennie I. Osburn. CRC Press. Inc. Boca Raton. Florida 33431. 646-650.

More information:

www.mapa.gob.es/es/ganaderia/temas/sanidad-animal-higiene-ganadera/sanidad-animal/enfermedades/lengua-azul/lengua_azul.aspx

www.oie.int

ec.europa.eu/food/animals/animal-diseases/control-measures/bluetongue_en

Project Paleblu: www.paleblu.eu www.palebludata.com