African Horse Sickness (AHS)

What is African Horse Sickness?

African Horse Sickness (AHS) is a non-contagious infectious viral disease affecting horses, both domestic and wild, and whose distribution is related to of the vectors of genus Culicoides. The etiologic agent is the AHS virus (AHSV) that belongs to the genus Orbivirus, as the Bluetongue Virus (BTV) and epizootic haemorrhagic disease virus, which have similar characteristic. Nowadays, nine antigenically different serotypes have been described by virus-neutralization but some cross-immunity has been observed between 1 and 2, 3 and 7, 5 and 8 and 6 and 9, but no with others orbivirus.

The main hosts of the disease are horses, mules, donkeys and zebras. These have different susceptibilities. Horses have a mortality rate of 50-95%, followed by mules with mortality around 50%. In enzootic regions of Africa, donkeys are moderately susceptible and experience only subclinical infections. However, in European and Asian countries, donkeys are moderately susceptible, and their mortality rate is 10%. Zebras are the natural reservoir of the disease in Africa, thus markedly resistant with no clinical signs, except fever. Dogs can be infected experimentally or by consuming contaminated horse meat.

The disease occurs with a seasonal (late summer / autumn) and cyclic incidence, appearing the major epizootics in southern Africa during the warm season associated with the presence of the vector. At least two vectors are involved in its transmission: Culicoides imicola and C. bolitinos, although it is believed that C. pulicaris and C. obsoletus may also be potential vectors due to they had been the responsible species of the BTV spread in northern Europe.

Historical evolution of the disease

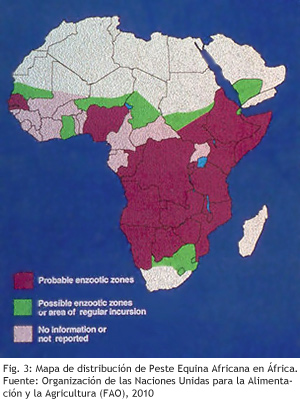

African Horse Sickness (AHS) is enzootic in tropical and subtropical regions of Sub-Saharan Africa and Yemen, where outbreaks of disease are regularly reported in domestic equidae. The first reference of the disease was an outbreak in Yemen in 1932. However, the virus probably was originated in Africa.

There are no references to the disease in South Africa until 1657. In 1719 the first major outbreak occurred with more than 1,700 dead animals. Different AHS outbreaks had been reported since its discovery to the present, highlighting the outbreak that occurred in South Africa (1854-1855) in which 70,000 horses died. During the last century, the frequency, extent and severity of outbreaks significantly dropped in this area, coinciding with a decline in populations of horses and zebras and the development of vaccines against the disease.

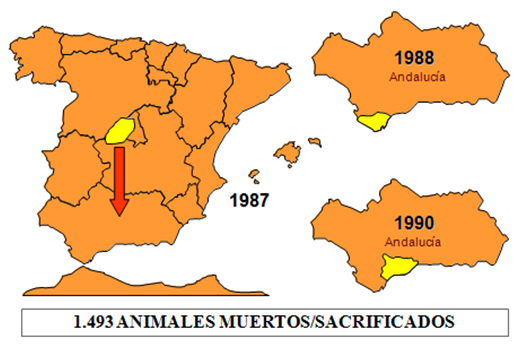

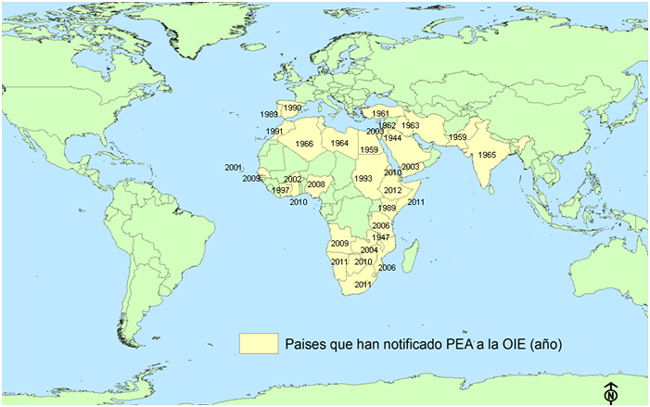

In the distribution area of competent vectors but outside the endemic area, several sporadic outbreaks have been reported in the last century. In the period 1959 to 1961, serotype 9 affected many countries in the Middle East, getting its eradication through mass vaccination campaign. In 1965 the same serotype appeared in Morocco, after spread to Algeria and Tunisia, and crossed the Strait of Gibraltar, arriving to Spain in October 1966. Spain achieved viral eradication after application of an intense vaccination campaign. Until 1987 no outbreak were declared in non-endemic area, being reported this year an AHS outbreak of serotype 4 in Spain. This outbreak was caused by the importation of subclinical infected zebras to a safari of the Community of Madrid. Outbreaks lasted until October in the centre of the country. However, secondary outbreaks were declared in the South, which were not eradicated until 1990. In 1989, the outbreak in Spain spread to Portugal, which eradicated that year, and Morocco, where the virus remained until 1991.

Since 2010 the countries that have reported the disease to the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) were Botswana (last notification in 2010), Eritrea (last notification in 2010), Ghana (last notification in 2010), Lesotho (last notification in 2011), Namibia (last notification in 2011), Somalia (last notification in 2011), Swaziland (last notification in 2011), South Africa (last notification in 2011) and Ethiopia (last notification in 2012, the endemic disease has been declared).

Fig.5: African horse sickness geographical distribution. Data: Based on data published from the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE).

Despite health measures performed at the borders of the European Union (EU) the AHS recurrence is possible in our country due to the incessant movements of horses for sport competitions or trade and transmission by vectors, since they can move long distances and have increased their range due to global warming. The presence of this disease in a country causes important restrictions on equidae trade, seriously affecting economic, sports and cultural activities.

Diagnosis of the African Horse Sickness

With the emergence of an outbreak, early suspicions are based on clinical signs and prevalence of vectors in the area. However, laboratory diagnosis is essential to establish a correct and confirmatory diagnosis. This diagnostic is prescribed by the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) in Chapter 2.5.1 of the Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial. They can be divided into two groups:

With the emergence of an outbreak, early suspicions are based on clinical signs and prevalence of vectors in the area. However, laboratory diagnosis is essential to establish a correct and confirmatory diagnosis. This diagnostic is prescribed by the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) in Chapter 2.5.1 of the Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial. They can be divided into two groups::

Identification of the agent:

- Isolation of AHSV in cell culture, in embryonated eggs or in newborm mice.

- Virus neutralization test for virus of AHS (AHSV) serotyping allow the identification of virus of AHS’s isolated from the field using type specific antisera.

- Serogroup-specific sandwich enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay (ELISAs). Two techniques have been developed; one uses polyclonal antibodies (PAbs) to the virus of AHS (AHSV) and the other uses monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) against protein VP7.

- Chain reaction polymerase (RT-PCR). An RT-PCR assay for the specific detection of AHSV genome has been developed. More recently, a new type-specific RT-PCR for identification and differentiation of the nine AHSV serotypes has been designed.

Serological tests:

- Complement fixation test.

- Indirect ELISA for antibody detection:

- Indirect and competitive ELISAs using a recombinant protein VP7 as antigen.

- An indirect ELISA is also available that uses the AHSV serotype 4 nonstructural protein NS3 as antigen.

- Immunoblotting.

- Serotyping by virus-neutralization detecting serotype-specific antibody of AHS virus.

Prevention and control of African Horse Sickness

World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) establishes in its Terrestrial Animal Health Code (Chapter 12.1, African Horse Sickness) what kind of measures should be carried out against African Horse Sickness (AHS). These measures are included in the European Union (EU) (Directive 92/35/EEC) and national legislation (Manual Práctico de Operaciones en la Lucha Contra la Peste Equina Africana). The recommendations contained in these legislations are based on:

- Notification to the competent authorities of all suspected cases.

- Restriction of animal movement from the farm or farms concerned.

- Establishment of a protection and surveillance zones around the farm or farms concerned, 100 and 50 kilometers, respectively. These distances are higher than those established for other diseases EU listed, with the exception of Bluetongue virus, because both have the same transmission by mosquitoes of the genus Culicoides. The size of these areas can be modified by geographical, climatic and entomological conditions.

- Confinement of animals during the maximum activities of vectors and vector control measures using insecticides and repellents on the environment, in the accommodation of animals and the animals themselves.

- Use insecticides and repellents on animals, farm and vehicles with special attention to other species such as cattle or sheep, which can take with them infected culicoides.

- Implementation of clinical, serological, epidemiological and entomological in the areas of protection and surveillance zones established around the outbreaks.

- Vaccination programs of all equidae locate in the protection zone.

- Programs entomological surveillance through trapping, allow us to know the species of culicoides which can transmit the disease.

- Serological surveillance programs allow early detection of the presence of the disease.

Vaccination is the most effective measure to minimize losses associated with the disease, eventually interrupt the cycle of the animal to the vector and allow the eradication of the disease. There are several types of vaccines against AHS:

- Live attenuated vaccine polyvalent or monovalent: It has a general use. They are prepared by the Institute Onderstepoort (South Africa), among others. There are two types approved by OIE, a trivalent vaccine (serotypes 1, 3 and 4) and another quadrivalent vaccine (serotypes 2, 6, 7 and 8).

- Monovalent inactivated vaccine. The Research Center for Animal Health (CISA-INIA) developed an inactivated vaccine against serotype 4. However, it is not currently available.

- Recombinant subunit vaccines, employing protein VP2, VP5 and VP7 as immunogen and expressed in the baculovirus system. However, this vaccine is not commercially available.

Vaccination in Spain

One of the control measures against the African Horse Sickness (AHS) is vaccination of uninfected animals of susceptible species together with their identification, only if the applicable law allows it (see Prevention and control of disease). Vaccination strategies in a zone must include all animals of the genus Equus (horses, donkeys, asses, zebras and onagers).

This measure will also ensure long-term eradication of the disease. The fact that an animal has been vaccinated against one AHS serotype does not totally protect against other AHS serotypes, since the vaccination only protects fully against the same antigenic variants.

In Spain, we used two types of vaccines for the control and eradication of the disease. At the outbreak of 1966 in Campo de Gibraltar a mass vaccination of 600,000 animals was carried out with polyvalent live attenuated vaccines, achieving the eradication of the disease in December 1966. Similarly, at the outbreak of 1987-1990 eradication of the disease was also achieved through vaccination. In 1987 and 1988, the campaign of vaccination was made with polyvalent live attenuated vaccines. However, in 1989 the vaccination was performed with monovalent inactivated vaccines. In December 1993, Spain was declared AHS-free.

Further information

http://www.oie.int/es/

http://web.oie.int/wahis/public.php?page=home

http://rasve.magrama.es